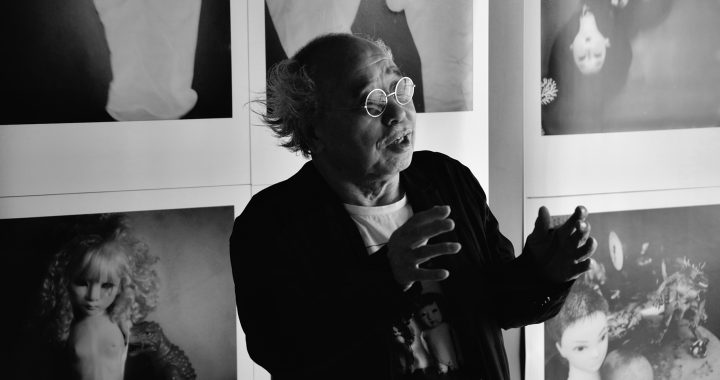

To photograph humans passing out from this world requires a strong character and courage. To catch such story inside your family and more even in the closest family circle, a big portion of a vulnerability is a must. Nancy Borowick in her series shows all above. The pain is shifted to kindness, all in a gentle package as a form of therapy. She depicts love to her parents and fear from their death in a very personal confession. Nancy has been awarded with many prices, including 2nd prize in the prestigious World Press Photo Award’s 2016 category for Long Term Projects. We talked about her life and inner power to continue.

Did you always wanted to become a photographer?

I was always a curious kid. As a child I had no problem walking up to complete strangers and striking up conversation with them. When I picked up a camera in highschool, it became clear almost immediately that this would quickly become the intstrument through which I could express this curiousity. I was always a visual person, and through the camera viewfinder I could observe the world around me and capture the moments as they passed by. I was also always a nostalgic person, and still am today, so the desire to hold onto memory has been a part of the fabric of my being since the beginning… and photography was and is the tool that allows me to hold on and remember.

Beside photographic education you also have a degree in anthropology. Do you use this knowledge in your documentary?

Anthropology is the study of human society and culture, and I think I have been a student of this my entire life. In college, I was drawn to anthropology because it allowed me to dig deep into communities I was less familiar with and using this knowledge and context as the driving force behind my image making seemed like a no-brainer. I didn’t know much about photojournalism but my interests in both anthropology and photography seemed to marry perfectly under this umbrella.

Why did you choose documentary and photojournalism?

To tell the most honest and authentic story, I believe you need to really dig deep. What I love about documentary and photojournalism is that you are always going beneath the surface level or a story, searching for truth and the human connection. I need that connection and it feeds my passion and drive to push forward and tell important stories. Also, to be able to see that the work I do informs others and can create an awareness about an issue and ultimately have a real impact on others lives… there is nothing more beautiful and humbling.

His and Hers. Dad called these “his and hers chairs.” He would sit beside Mom, his partner and wife of thirty-four years, as they got their weekly chemotherapy treatments. He had just been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and she was in treatment for breast cancer for the third time in her life. For him it was new and unknown, and for her it was business as usual, another appointment on her calendar.

Last year you have published your first book „The Family Imprint“ based on your photography essay „Cancer Family“. How was the book tour? Or are you still touring?

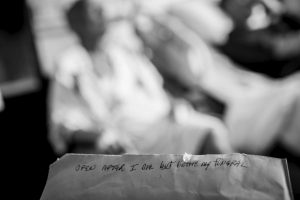

Yes so The Family Imprint is the manifestation of both the Cancer Family story that I shot but also digs deeper into those layers I talk about before. The story I shot, while my parents were in treatment, focused on our life and living during the time of their illnesses. After they died, I went on a personal journey, digging through old family photographs and memorabilia to better understand who my parents were, the lives they lived before cancer, and learn more about myself in the process. What I found were these beautiful keepsakes they held onto, like notes they wrote to each other, objects they cherished. I also found notes and journals where it felt like they were still talking and guiding and parenting me, even though they were gone. I felt the need to put all of this together in a form of a scrapbook (we love to scrapbook in my family) because I think the most authentic version of this whole project is the larger story, the before during and after, because life exists before just as it exists after, and these pieces amplify the work that I did. I felt the need to share the story in this form and to do that, I sent myself on a book tour. I asked the facebook universe where I should go, and people chimed in, offering their spaces and their help as long as I could get there. This took me everywhere from northern Sweden to coastal Australia, and I will continue to tour with the book as long as people will have me! Maybe Slovakia next? Let me know! The experience of sharing with others, and hearing their personal stories, was tremendously powerful and healing for me, and hopefully for them. Going through what I went through can sometimes feel lonely so to feel a sense of community, even from complete strangers, is truly a gift.

Creation of a photographic publication is very specific and photographer can spend a lot of time to build a story by choosing the right pictures. Your book is unique, it contains also memories of your family, hand notes, cut pictures and has its specific design. How long have you been carrying this idea in mind?

The idea didn’t really take hold until people started to ask me, “How did your family do this? How were your parents so strong? How was there so much joy in such a sad time?” In trying to answer these questions, I needed to go back and learn about my family from a time before I even existed. This was just my normal, the way in which my family dealt with our situation, but hearing that this is not the norm always, I wanted to better understand how we came to this place. One important thing I learned was that both of my parents lost parents from cancer at a young age and this impacted the way in which they viewed their time on Earth. They both understood the fragility of life and how each day is a gift, and I think this largely impacted the way they lived each and everyday, and also kept things in perspective. They taught us kids so many lessons in this time, and I am so lucky and grateful to them, which is also why I wanted to share these lessons with others in the book.

In the essay „Cancer Family“ you captured the final years of your parents struggling with cancer. It`s one of the heaviest themes for a photographer to take. This series was also recognized globally (WPP 2016). Is this essay some redemption or therapy for you?

Absolutely this was therapy for me. I had never experienced this kind of loss before and I was scared. By photographing our lives, I was able to use a familiar context (photography) through which to understand and process what was happening. I spent most of my days with a camera in front of my face, so it made sense to continue this practice and it wasn’t until later in the story that I realized just how valuable that camera was for my sanity, allowing me a bit of emotional and physical distance from the realty in front of me as my parents were dying.

Happy New Year. No matter how many times her cancer returned, Mom finds a way to live her life and not take it too seriously in spite of this reality.

From this essay is obvious that other members of your family have been supporting you. Were there some moments they told you to stop, “Do not shoot me!”?

Fortunately, there were rarely moments when people in the family asked me not to shoot. There was a moment early on when my dad had a particularly rough day of treatment and he asked me why I took so many photographs. His tone was almost accusatory, but then he moved passed it, because it was just a fleeting moment when he was feeling vulnerable and weak. After that, he seemed to even encourage me more to shoot.

Where did you get inner power to build such intimate and powerful story? What was the main motivation to carry on?

To be honest, I look back on the images and wonder how I did it. I think I was so in the moment, going through the motions, and in some ways, maybe disconnecting from the reality a little. By photographing my parents, I subconsciously put on my photographers hat and worked the scenes, noticing the light and the composition and some how not focusing on the pain in front of me. I think maybe it was a defense mechanism, but whatever it was, it helped and protected me from completely falling apart. What good would I have been to my parents if I was a mess? I had no medical expertise to share with them so maybe if I could tell their story, our story, that gave me purpose in this time.

What was the reaction of public after your family story had been featured in The New York Times? Did you expect such a huge feedback?

None of us could have imagined or predicted the engagement after our story was in the New York Times. It was truly overwhelming. People from around the world, from all different walks of life, reached out on every communication platform. They wanted to thank us for being so open, send prayers and well wishes, and to share their own stories. I think hearing these stories, my family felt less alone in our struggles but also, in some ways, I think seeing the impact our story made gave my parents a greater sense of purpose in their lives as they approached their deaths. It wasn’t all for nothing, you know? They helped people, and that was comforting.

In your long term project “Part of the Pack” you show strong relation between human and dog. What is the other one “8 Years with Maame K” about?

Anyone who knows me knows that I am a bit of a crazy dog lady. I love dogs, and I feel a certain connection to them. They have always been a therapeutic outlet for me, especially after my parents died, so that project made sense. 8 Years with Maame K is the story of a young girl in Ghana who I met, well, 8 years ago. I was living in Ghana for a few months after graduating college and I was teaching photography at a rural school. Maame K was my student and she took to me, and I her. For 8 years I was fortunate enough to return to Ghana for NGO work and each time I returned, I would visit my old school and see her (and photograph her). This project is on going as she is now in high school looking towards university and we have struck up a great friendship. I didn’t realize I had those ongoing project until recently when I went back through my images.

The term long-term is, in my opinion, not just about time spending by taking pictures. The more important is how deeply is photographer able to immerse in and become familiar with the topic. What is your approach?

My approach is to not overthink it and let things happen organically. Whenever I have forced myself and put pressure on myself to work on a specific project, and within a short period of time, you can feel it in the images I produce. As with any relationship, it takes time to get to a place of trust and vulnerability so if you have the luxury of time, take your time. The more your subjects trust you, the more they will let you in and reveal themselves. It is also important to remember that a relationship is a two way street and you have to give of your self as well in order to get something back. I have found that by being vulnerability and transparent has always helped me gain the access I hope for, and it has to be with good intention. Most of my photo subjects have become good friends of mine.

Do you have some, not meaning an idol, but a person whose creation is being very inspiring for you?

I am deeply inspired by the amazingly talented and passionate photographer Stephanie Sinclair. Her work and life long devotion towards using photography to raise awareness and bring change in the space of ending child marriage is a constant inspiration. The work is far from easy, but she never seems to let up, and because of her commitment to this issue that is not an easy one, visually or emotionally, she has seen and brought change and freedom to the lives of countless young women around the world. I am inspired by her never faltering drive for truth and justice.

Holding On.

All eyes were on her chest as she took her final breath. And then it was over. No more breaths. Mom’s brother, a doctor, checked her pulse, then a friend, also a doctor, followed suit. They called it: she was gone. There were tears of sadness, tears of exhaustion and tears of relief filling her bedroom that afternoon.

Do you currently have a new long-term project to work on?

I do. Sort of. I am living on the island of Guam, which is a US Territory in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and I recently started photographing a story that has got me really excited. It is the story of family (no surprise there), looking at the everyday life of two young men, recently married, who just started raising a son whom was born through surrogacy. They also happen to be magicians and have an amazing show, together, sharing the stage here in Guam. I have been interested in photographing the magic in their everyday lives, on and off the stage. It is hard to find projects that inspire me without putting too much pressure on myself following my family story, but this one brings me joy and it has me exercising my shooting muscles again and I think that is important!

What are your future plans?

Oh wow. Well, as a photographer I hope to continue to work on projects that both inspire me but also can bring about change and awareness in the world. I also hope to find some balance, maybe have a family of my own, and figure out a way to make everything work. This life is too short, and I want to make the most of my time as I can. I learned this from my parents and I continue to live each day the best I can.

Nancy Borowick (*1985) is a humanitarian photographer based on the island of Guam and New York City. She is a graduate of the Documentary Photography and Photojournalism program at the International Center of Photography and holds a degree in Anthropology and Photography from Union College. In 2008, she established The Ghana On Tap Project, raising funds and overseeing the drilling of a borehole well at an orphanage in central Ghana and since 2009, she has worked closely with the Touch A Life organization, a non profit that provides holistic care for children rescued from slavery and trafficking in West Africa. Nancy’s most recent focus has been her parents’ parallel diagnoses with cancer, which culminated in her monograph, The Family Imprint, published with Hatje Cantz in 2017. She has received numerous accolades for the book and the photo series, including recognition as a winner in the Photo District News Photo Annual, a top finalist in the Pictures of the Year International competition 2018 as well as in the International Photo Awards competition. Her work took the top honor in the Arnold Newman Prize for New Directions in Photographic Portraiture and she ultimately took home the 2nd prize in the prestigious World Press Photo Award’s 2016 category for Long Term Projects. She has recently been announced as the 2018 recipient of the Women That Soar Humanitarian Award. The work has also been exhibited internationally in over 100 cities and Nancy has brought her story to universities, health care centers, oncology units, and community groups around the globe. Nancy is a regular contributor to the New York Times and has also been featured in the New York Times Magazine, CNN, National Geographic, Time Magazine, Photo District News, the Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, O The Oprah Magazine, Glamour Magazine, Stern Magazine, Newsweek Japan and many others.

All photographs © Nancy Borowick.

In Sickness and In Health. On their wedding day, they vowed to be together, in sickness and in health and until death would they part. Upon death they may have parted, but I believe they are now back together, side-by-side. Two years after Mom’s death, we gathered to honor both of them, and leave stones as signifiers that we were there and that we remembered them.