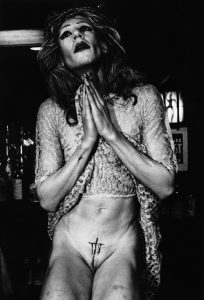

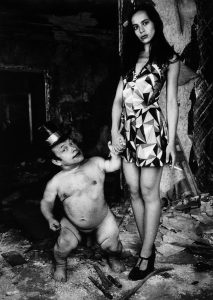

Individualism and the unconventional beauty portrayed throughout Zownir’s raw and unbiased view of life and death often exceeds the limits of decency and good taste. His expressionistic black and white photograph offers insight into inner-city sub-cultural spheres – into the shadowy world of individualists and outsiders.

Exhibitionists, homosexuals, prostitutes and homeless people. Subjects and small communities that are excluded and rejected by our societies captured on mysterious, grotesque, and indiscreet shots. Without censorship, Zownir reveals to the bone what remains hidden to us behind the bedroom and brothel doors, in the dark and narrow aisles of human cities and lives. Dark and gloomy photographs present the viewer with intensively disturbing and indiscrete shots of the lust, violence, insanity, absurdity, and man’s obsession on the brink of society.

It is almost impossible not to feel an intense emotional response when facing Zownir’s photographs. His definition of beauty differs from the mainstream. Attractiveness is more important than beauty itself, and subjects on monochrome photographs are authentic. The mysterious sense of timelessness captured on Zownir’s shots leads the viewer into a different reality – terrible and cruel, reflecting all negative characters of human beings.

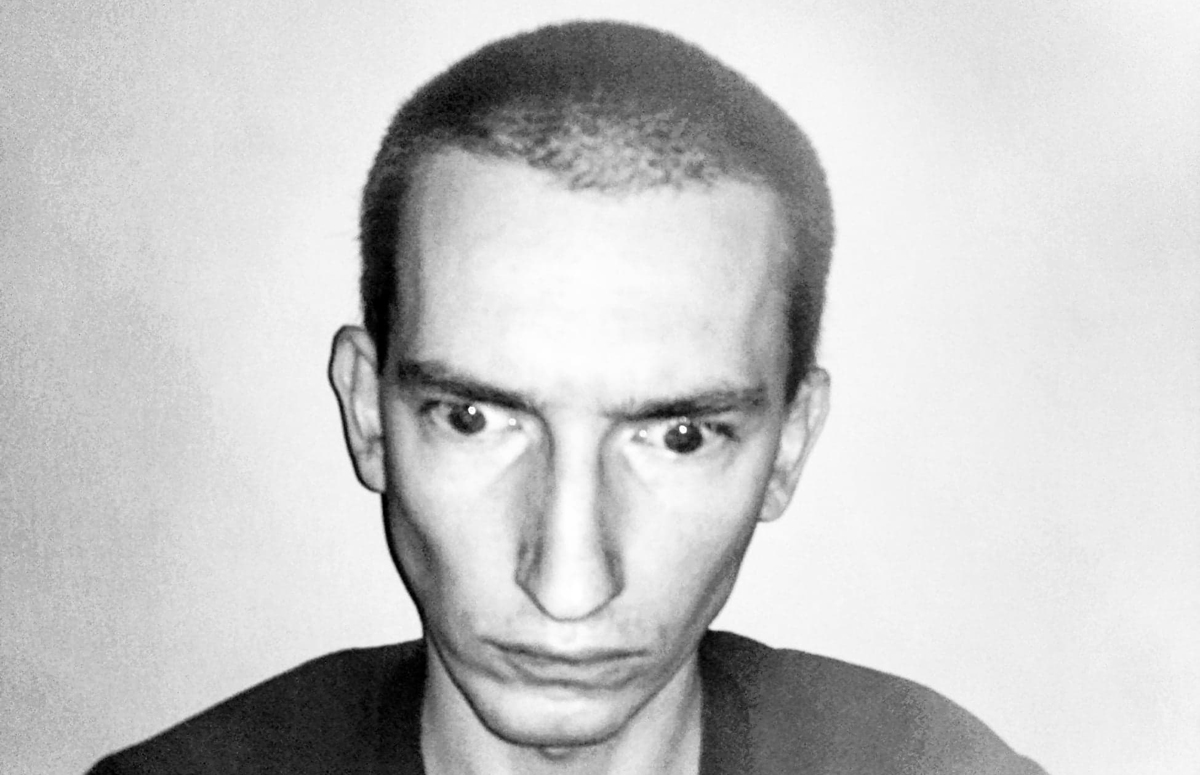

The label “Poet of radical photography” given by Terry Southern carries a partial definition of Zownir’s work. He is a poet, he is radical and he is a photographer. But Miron Zownir is a lot more than a few words can express. He will take you back in time, into the world that no longer exists.

Your father was Ukrainian, but you grew up in post-war Germany. How did your family end up there?

My mother is German. My father’s family was Ukrainian and had been deported to Siberia during the Stalin era. My father fled to the West, got drafted into the German Wehrmacht, later he was imprisoned in a Russian war prison and met my mother in the early 50’s in West Germany. His life was quite an Odyssey.

Since you are of a Ukrainian descent has this influenced your identity, who you are?

There are so many things that influence your identity. I didn’t have any advantages or disadvantages growing up in post-war Germany having a Ukrainian name or father. But from an early age, I was very interested in Russian literature and in Eastern Europe in particular. It was the time of the cold war but for me, the people in the East were never my enemies. I didn’t like nor trust either system, neither the Western nor the Eastern one. I didn’t trust politicians or any social stereotypes and I was always interested in individualists.

In what way has the post-war atmosphere shaped your creation of photographic images?

Any early childhood impression shapes your future outlook on life. When I was born the World War Two was already eight years over but many traces of it still remained. Ruins, war veterans, disabled and injured people. Where I grew up for the first six years sanitation was poor and even the sewerage water system wasn’t developed until the early 60’s. It was a time of transition and hopes. Looking back at it I would say it was rather gloomy and strange but not necessarily depressing. I was an observer and dreamer and my imagination went far beyond the boundaries of my grandparents’ home. Let’s say this early post-war atmosphere was very influential in shaping my character, the way I developed, my creative spirit, and my approach to the photography.

Did you study arts or photography?

No, I’m a self-taught person in everything I create. I`ve never liked schools and I`ve never had any inspiring teachers.

Diane Arbus?

Well, yes, I like her. But I started to discover great photographers only after I had already developed my own style. My themes were from the beginning what they still are. I didn’t have to study other photographers to find out what I am interested in or how to capture an interesting photo.

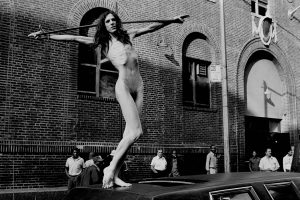

Naked women and men. Sexual intercourse. Masturbation. You reveal intimacy of a human being in its most direct and detailed form. What do you think about invading in another person’s privacy with your camera?

If someone exposes himself/or herself in public I don’t invade their privacy. And if I’m invited to someones home it’s up to them how far they want to go or expose themselves to me. Most of the people I made photos of in any sexual context were exhibitionist or they wouldn’t have been masturbating, fucking or whatever in public or in front of my camera.

How do you manage to get into intimate space of such tightly-specified group of people? Do you get to know them?

I have been close enough living in slum-like places. I didn’t have a profession, no regular income, no lobby, no financial backup and no existential security. I was wild, daring and cocky. I was as much a social outsider or outcast as any of the people I made photos of. I had an anti-establishment attitude and an open mind. It was easy for me to gain trust because I was sincere. I didn’t have to slime or bullshit my way into any photographic relationship. I never did. In the last years, my focus was more on the outside, making mostly photos of anonymous situations.

What were the reactions of public on your photographs?

Different. I got lots of praise in the subculture and was mostly ignored in the mass media. Until recently it was always only a few women or men that had the guts to exhibit or publish me. I guess I’m more and more recognized as a groundbreaking artist or photographer. But I’m sure there are still enough people who think what I’m doing is morally wrong and should be banned.

So, has censorship on various platforms been a frequent companion of your career as a photographer?

Of course. What established magazine you know of would publish someone with an erection or people having intercourse? And the pornographic papers are not interested in people starving or suffering. A gay magazine is only interested in a good looking men and a women’s magazine in good looking women, celebrities, big shots you name it. It’s only in the last couple of years that some lifestyle mags got more open and daring such as the „Zoo Magazine“, „Dazed &Confused“ and some others. Thanks to the internet more and more open-minded platforms got established. But even 10 years ago it was much harder for me to get published or exhibited other than in underground platforms.

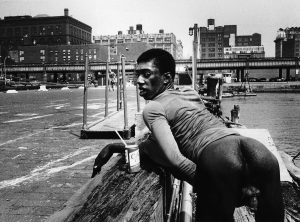

Why did you choose New York as another place to create in after Berlin?

It was at that time the world’s most fascinating place. Crazier, wilder and more cosmopolitan than any other city. It was a time of emancipation, the sexual revolution, and artistic experiments. You could feel an almost lawless hedonistic spirit hyped up by drugs and overrated egos. Everything seemed to be possible and limitless until Aids become a reality and frightened everybody.

Those people you photographed may already be dead. How does it feel like to look back at those photos?

Of course it makes me sad that so many people died of Aids. In the 70’s or the early 80’s, nobody was aware of the risk. And once infected it was too late. Until the early 90’s Aids was a death sentence. Some of my best friends died of Aids. The price they had to pay for sexual freedom or injecting dope was so fucking high. It’s insane…

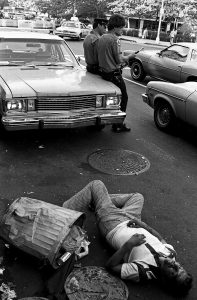

Several of your photographs from New York capture also police officers. What was your relationship with them and how did they respond to your presence?

I never had any relationship with the police. Some ignored me, some tolerated me and some others hated my guts. I got several times arrested for shooting photos at the wrong place at the wrong time. I wasn’t a Weegee fraternizing with them.

Your street photographs from Moscow, which depict homeless people, dying, and the death in public, reveal an apparent social and moral decline in the former Soviet Union. How did you perceive this metropolis at that time, and what feelings it left you behind?

It was a feeling of total helplessness, anger and sadness. I never felt it was enough to document this misery. But what else could I do? Close my eyes and pretend everything was cool?

This preoccupation with portraying life with all its cruelty, its absurdity, its unconventional beauty and with extreme individualism, where does that stem from?

From my unwillingness to ignore the reality, censor the truth, bend to public expectation or preferences. I always expressed what I wanted regardless of its consequences. That’s something neither my German ancestors growing up in Nazi Germany or my Ukrainian ancestors living under totalitarian governments could afford to do without risking more than I did.

You took pictures in West Berlin and London in the 70s, in New York and Los Angeles in the 80s, in Moscow in the 90s and after you were again shooting in Berlin. Are another of your upcoming photographic projects situated again in a city?

Last year I documented life on Skid Row Los Angeles and in the Tenderloin District of San Francisco. This year I went to England for a photo trip, next year I’ll be in Romania and maybe I get a grant to make a photo book about Rome.

Do you consider yourself being The Poet of Radical Photography as once labeled by Terry Southern?

This is a label given to me. It sounds ok but I live up to my own standards. Am I a poet? Yes. Am I radical? Yes. Am I a photographer? Yes. But I’m a lot more than a couple of words could express.

What is the motivation of your work?

Isn’t it obvious?

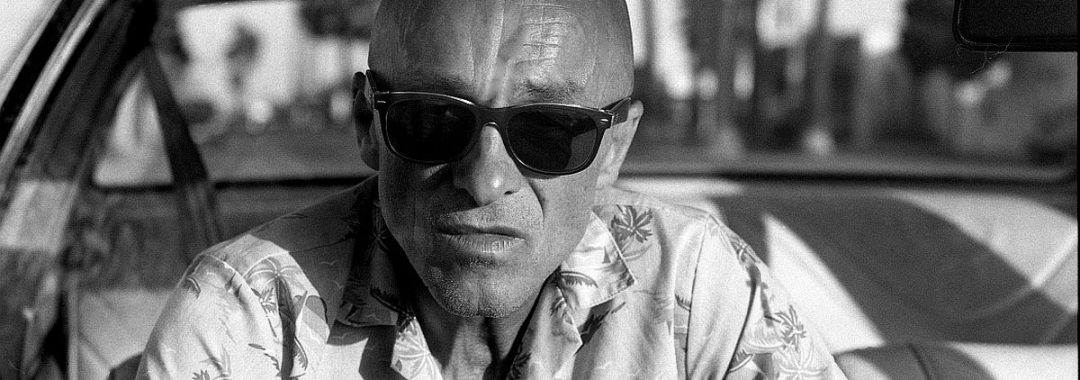

Photo on the top by © Gregory Bojorquez.

Miron Zownir (*1953) is a German photographer, director, screenwriter and writer, currently living in Berlin. He was born in Karlsruhe in a German-Ukrainian family. The subject of his work is the reality of man on the edge of society surrounded by his obsessions. He took up photography during the peak of the punk phenomenon in the late 1970s, in Germany and England, and later he documented the hidden New York subcultures and homeless crisis in Moscow. He is the author of movies Bruno S. – Die Fremde ist der Tod (2003), Phantomanie (2009), Back to Nothing (2016) and books Down & Out in Moscow, NYC RIP, Berlin Noir, Radical Eye: The Photography of Miron Zownir (1997), Kein schlichter Abgang (2003), Parasiten der Ohnmacht (2009), The Valley of the Shadow: The Photography of Miron Zownir (2010) and Ukrainische Nacht (2015).