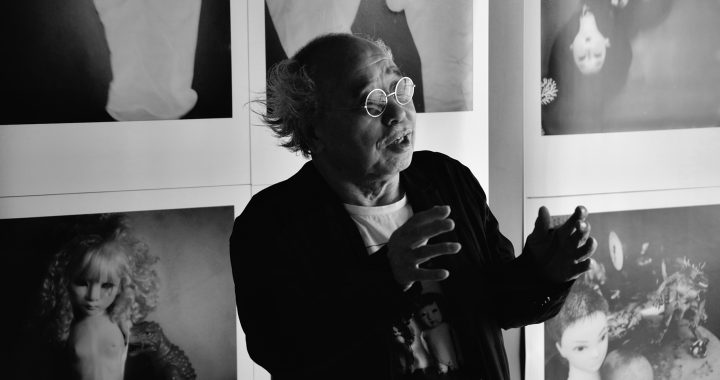

Hans Madej is a man locked in the tesseract of history. Through his work he explores how the echoes of our familial and social past resonates within us in ways both apparent and subtle, as well as how the oppression of few affects the lives of many. Madej learned how to photograph from his father, a shell-shocked soldier who witnessed the horrors of the Eastern Front in World War II – horrors so great that they eventually led to his suicide. Madej found that as he turned his camera outward to the parts of the world being left behind by modernity, as well as grappling in the wake of modern wars, his own past was reverberating within him and gently calling out. Throughout his career Madej followed in the invisible footsteps of his own family history though he would not be made aware of it for years to come. That is what makes Madej’s work so ineffable – the fact that it speaks so loudly without ever having to say a word and has, perhaps, been informed by a quiet force that cannot be heard, only felt.

Now Madej stands between his past and his future – a future where he moves forward with an eye to the destined and the erstwhile. It has taken Madej a lifetime to come to this point and as his audience watches his photography today unfold we will undoubtedly begin to see a deeper unveiling of a man who has always been so committed to bearing witness to the human condition as it rises up against all manner of dispute and intrigue.

You have had an impressively long career, what first drew you to photography? How did the images you were making back then develop into what you make today?

My father was a photographer. In 1945 he returned, traumatized, from the Eastern Front to a ruined Germany. He really wanted to be a pastor, but as fate would have it, he became a photographer. After the war, he exchanged photos of family farms for food. Later, he photographed weddings and made postcards of his work. He taught me his skills when I was young.

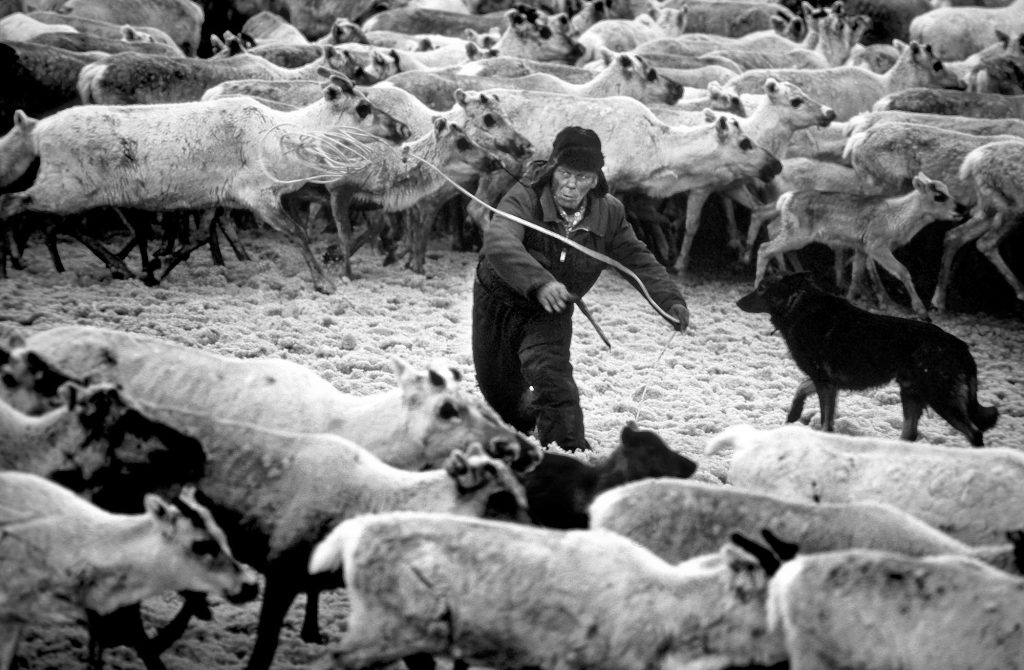

When I was 14, my father committed suicide. I inherited his darkroom and a Rolleiflex. Even though I later studied journalism and literary history, photography became the central content of my life from that point on. The decisive turning point came in 1978. At the age of 25, I travelled for the first time to the Greek Island chain of the Cyclades during the winter. It was cold, humid, and stormy. What I saw was bitter poverty and loneliness, but also contentment, human warmth and cheerfulness. I saw dying villages, inhabited by the elderly who stayed behind while their children chased after foreign influences and promises in Athen or abroad. It was the hopeless attempt of the older generation to preserve their identity between a history behind and a rapid future approaching them. It was a world that worked so different from my own: cruel and sad, but also simple and great. My images became a document of this barren and beautiful world whose years were numbered.

When I developed the first pictures a little later in my darkroom, it was clear to me that I had found my the central theme of my work and life; to document living conditions and structures that still exist, but were inexorably lost in the face of rapidly advancing changes. This episode already shows how I like to work; to capture moments filled with timelessness.

I lived on these islands for almost a year. These photos were also my ticket to a major Hamburg magazine publisher and the photographers association, Bilderberg, which united the best german photojournalists similar to the way Magnum functions. Ever since I completed my first story, my work has revolved around one of the basic fears of modernity – the fear of disappearing. I am drawn to archaic ways of life that are eradicated by uprooting and destroying structures through a blindly fortuitous progress. I want to do my part to keep these lost live forms alive in human memory.

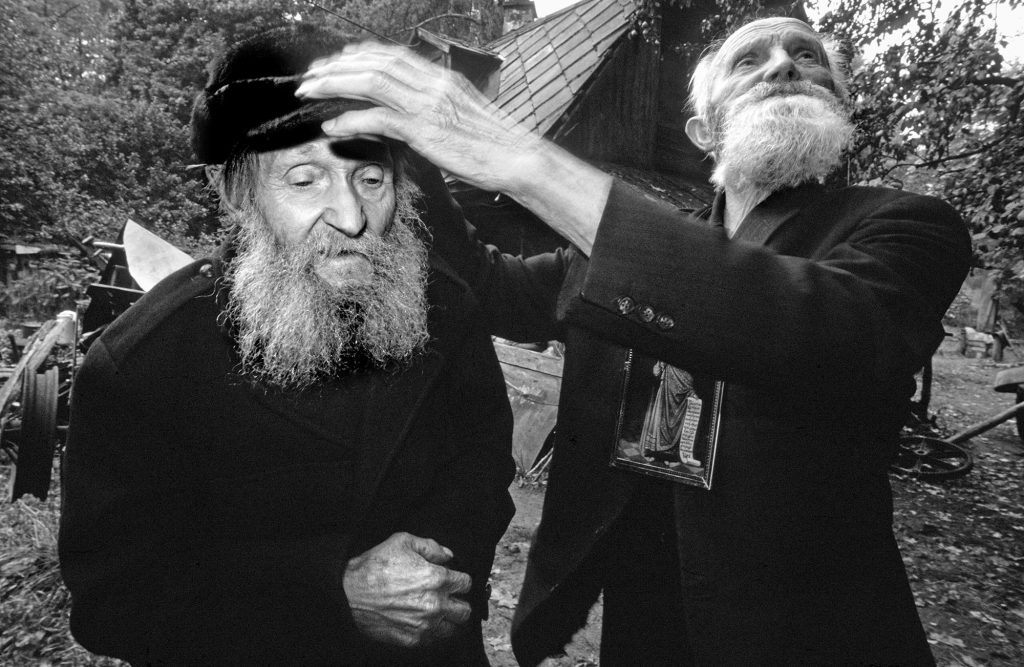

This way of searching for traces of history fascinates me to this day, only it has become much more personal and now refers much more to my own personal roots and origin, which have more or less unconsciously accompanied me on my travels for half a lifetime. I imagine all photographers, even if they travel the world, have a “soul home” somewhere. My soul home is clearly in the east of Europe. My mother comes from Czechoslovakia, my grandfather from today’s Polish – Ukrainian Galicia, a country that no longer exists on any map. I would like to once again, through my own family roots, search for the wounds and the hidden treasures of my origins. Where is home for all the people who were thrown like spears through world history? Those who are injured, wounded, sad, uprooted and brave – really brave.

You covered the political developments of Eastern Europe throughout the 1980s and 90s, which is such a watershed period for Eastern Europe and the effects of which are still being played out today. What drew you to these stories of political shift and how do you hope your images read to audiences today trying to understand what happened?

In 1986, I photographed for the first time in the East – in Budapest. I became acquainted with opposition supporters who dealt with the political and social problems in the Soviet bloc states. They were concerned with the fate of the German and Hungarian minority in Transylvania, Romania.

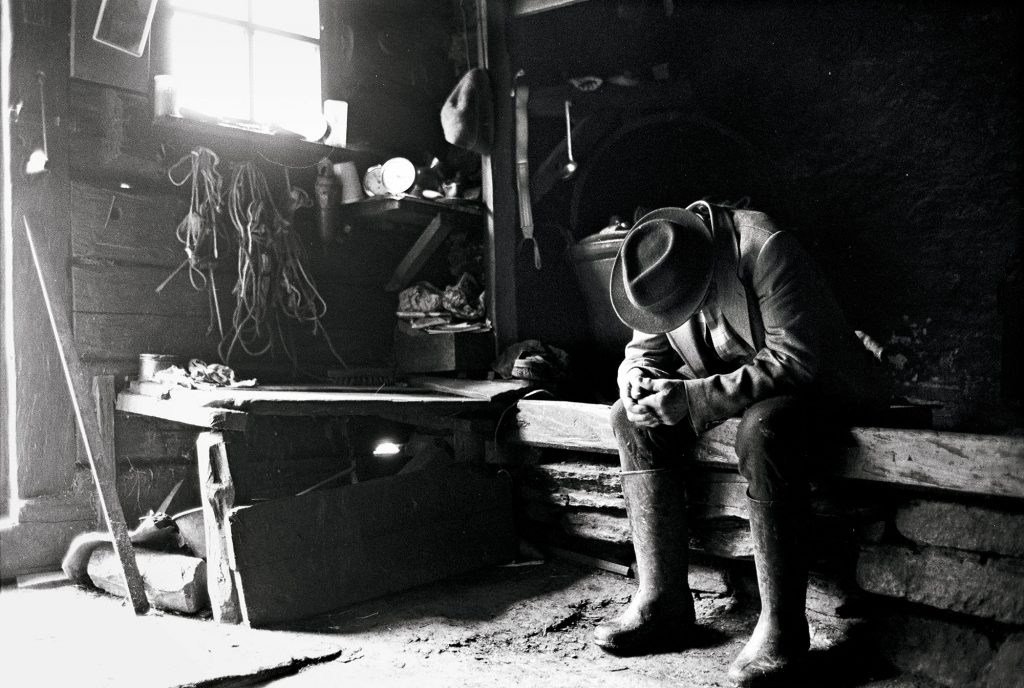

In a hitherto unprecedented campaign of destruction, Nicolae Ceaușescu, the Romanian communist politician and leader from 1965 to 1989, sent bulldozers to the countryside to wreck the old farmers’ villages. This “Systematization” project was issued at a time when the Romanian people were starving because the socialist planned economy had collapsed long ago. I traveled as a tourist with my girlfriend and dog in Romania, with a camera and a few rolls of film I smuggled across the border. I witnessed a merciless struggle for the “New Man” who, according to Ceausescu’s plans, was to enter the “Golden Age”. It was a nightmare of human contempt.

Ceausescu’s megalomania – related to most dictators – focused on decomposition. Decomposition as a precursor of destruction, decomposition of life plans, of friendship, of every kind of happiness. With my pictures I wanted to keep the memory of a way of life, for which there is no room in the modern world. And herein lies one of the central themes of my work, to expose the contradiction of a one sided future orientated world with memories of the past. Another central aspect of my images is the defense of the individual against the destructive forces of history. For me, a good photograph is the expression of the inadequacy of existence, regardless of whether or not it is in Eastern or Western context. A good picture describes the desire for a reality in which humanity is given more respect. Beyond all politics this is the message of these pictures for all those who did not experience the history I saw first hand.

You gave up photography at 41, can you talk about why you did that and how you eventually came back to it? What changed?

For more than 15 years I was traveling around the world as a photographer. I led a rushed life in the fast pace of picture making. In the meantime, I found myself without the opportunity to experience my own life for myself. That was, in the end, not why I became a photographer. I always wanted to contribute to the serious, thoughtful side of journalism, not the hunt for stories. And so, while I was doing reportage on the descendants of the former headhunters on the island of Sarawak in Malaysia for a magazine, I decided to end my raging reporter’s life.

My sympathy for those I was photographing had reached a confusing limit. I was classically burnt out. Finally, I realized that I needed to have time to think, to reflect – about me, about the medium of photography, and about the value of memory. I believed that the moving image was better suited to take the viewer on a journey so I started a new ambitious project. I wanted to film a story about a deserted village in Poland where I had photographed for GEO in 1992. For 5-years I worked on a film about the lives of some of the elderly people living there, and about their dreams and yearning for homeland and identity, and their desire for an ordered understanding of their history.

The people of this village in Poland had a history of being caught between Hitler in the West and Stalin in the East. They lived day to day with a need for spiritual clarity and and a means to create their “paradise on earth“ as I called it in the film. It was later nominated for the “World Television Award“ in the top 5 films.

During the making of this movie, I came across my own past. I came to a Polish village where my father was a Wehrmacht soldier in World War II. I remembered the few fragments my father and mother had told me about this time. I began to reconstruct my own family history. My mother was one of the displaced people of a whole population. She came from the Sudetenland, today’s Czech republic. My grandfather and generations before came from Galicia (today’s Poland). I drove through these villages, small villages, wooden houses, a garden, everything vibrating with memory. Though I had never been there before, and knew nothing of the past of my ancestors. It was only later that I explored the family’s own roots, where they came from – these villages. By chance I discovered my father’s military passport. The first entry was actually exactly the place in Poland where I lived during the filming. the last entry was Siberia, where the film took me on the search for a disappeared prophet in the Gulags, where my father was in Soviet captivity. the coordinates of the film and my photographic career were “coincidentally” the same I learned, like my father’s on the Eastern front.

I myself believe in genetic memory and sometimes I believe I did not live my own life, but was merely a witness to all those who lived before me: the father, grandfather, the ancestors, their experiences of war, poverty, displacement and death. These were often the contents of my photography and my film, and perhaps an answer to why it kept drawing me back to the common people, the archaic forms of life. I always wanted to preserve that. Through the progressive destruction of these structures through a blindly fortuitous progress, I wanted to play my part in keeping these disappearing forms of life in the memory.

You have mentioned going back and photographing in some of the locations you formerly covered. How do you expect the various two sets of images to compare to each other? Are you looking for anything in particular as you return?

As I mentioned at the beginning, my father died very early. After I stopped photographing I happened to discover his military passport from the Second World War. Oddly enough, many places of his wartime missions coincide with many places that I later visited as a photographer. This could be a concept for a long journey through the east, which I would like to photograph again without going into detail.

I will leave my explanation there for now as I try not to talk about future projects before they have been realized.

The photography industry is getting larger and larger, as well as much more competitive, but also diverse. What advice do you have for emerging photographers as they navigate their work?

As the photo industry grows in size, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to find photographers with their own vision. Today’s photographers are mostly photographic decathletes; they do a bit of everything. Hardly anyone anymore works on long term projects. I was primarily an assignment photographer. During my career, however, I made sure that I was able to pursue my person projects in addition to my photojournalism assignments.

Ultimately, good pictures are landmarks not only in the history of photography, but also in the history of human endeavors. Good pictures are always landmarks and not only in the history of photography but also in the history of human endeavour. These images share a compassion that is opposed to indifference of “cheap hope”. My photography is close to the people I work with, but also has a bit of distance because it needs to pay those portrayed respect. Even though the images I have made are now historical recordings, most of them still have a sense of the topicality of the timn. Is eastern Europe people still suffer from the problems that I photographed years ago. Anyone who strives to make timeless and honest images will sooner or later be rewarded and not soon forgotten.

Hans Madej (*1953) lives in Munich. He studied journalism, literature and art history before starting to take photographs as a self-taught artist in 1980. His photojournalistic work began in 1982 with reports and color essays for GEO, Stern, Merian and the Zeitmagazin. From 1987–1994 he photographed large-scale social and political reports on Central and Eastern Europe, which were published in Paris Match, Sunday Times and New York Times. He was one of the first western photographers who reported from Ceausescu’s Romania and Albania. He photographed the “gentle revolution” in Prague, the overthrow in Bulgaria, the opening of the Berlin wall and the Yugoslav civil war in Croatia and Bosnia, and finally the Chechen war. He wrote and photographed several illustrated books and his work has been shown at the international festival for picture journalism »Visa pour l’Image« and in the Willy-Brandt-Haus in Berlin. He has won the German Photo Award and the Kodak Photo Book Award. In 1995 he ended his career as a photo reporter and turned to film. “The photographed world,” he said, “may have the same fundamentally skewed relationship to the real world as the still photo to the film.” He made the documentary “Paradise on Earth”, which was nominated for the “World Television Award” in 2006. Hans Madej was a partner in the renowned photographer agency Bilderberg, later a member of the photo agency “laif”.

All photographs © Hans Madej.

Photo editor – Juraj Marec.

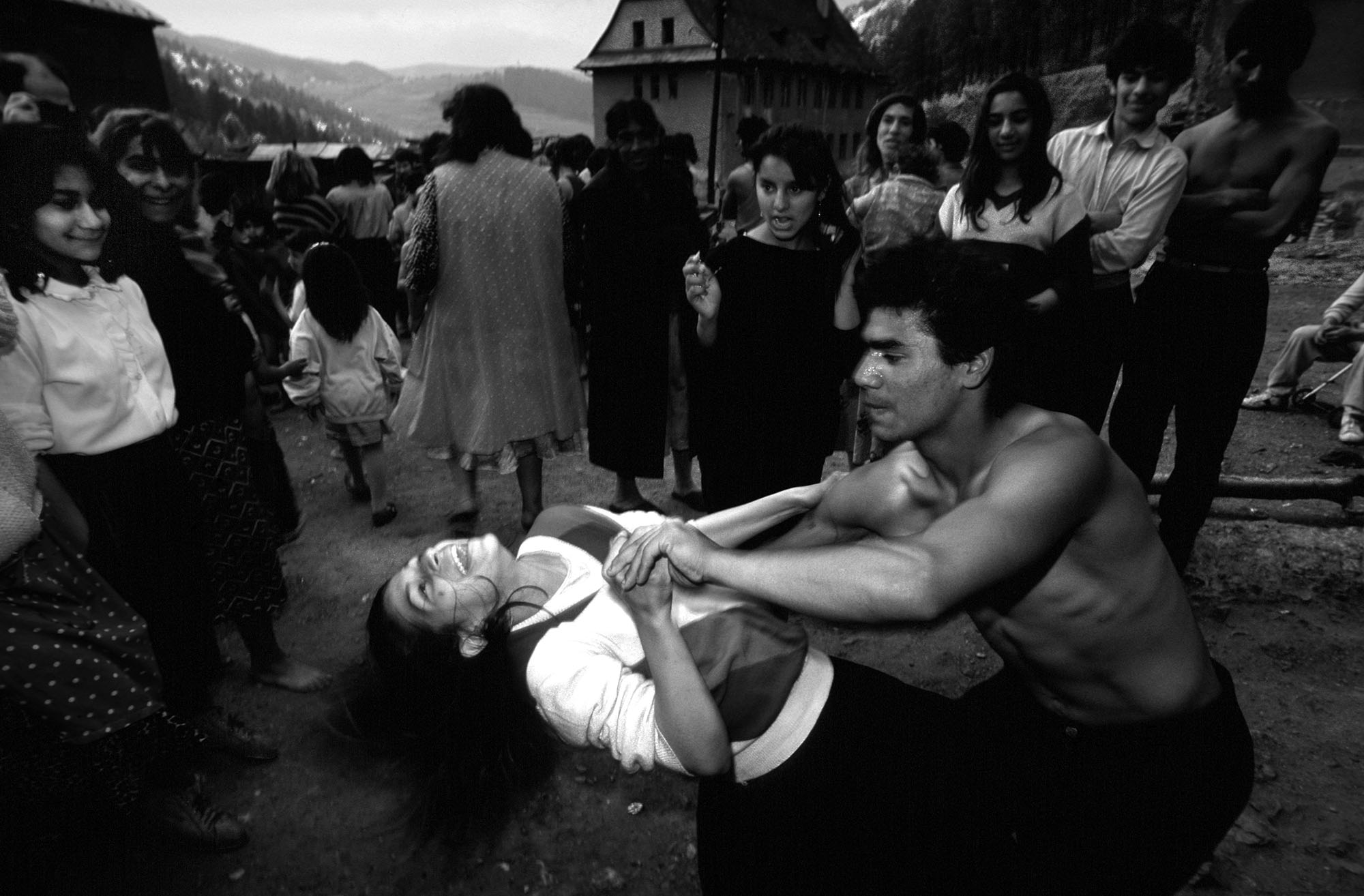

Roma, Slovakia, Rudňany, 1993